Jonathan O’Brien looks at what the coming food crisis means for all of us and how procurement functions must get creative to navigate their way through the challenging times that lie ahead.

We ain’t seen nothing yet!

There has been much written about the cost of living crisis but what we’re about to see will blow that out of the water. Put simply, we ain’t seen nothing yet!

Clearly, energy prices and those on supermarket shelves are rising. But many increases have not yet cascaded down to us. The gravity of what lies ahead isn’t understood. And it’s scary. We are heading for nothing short of a major food crisis that will land at the door of procurement functions in all sectors, particularly those in food, retail, and hospitality.

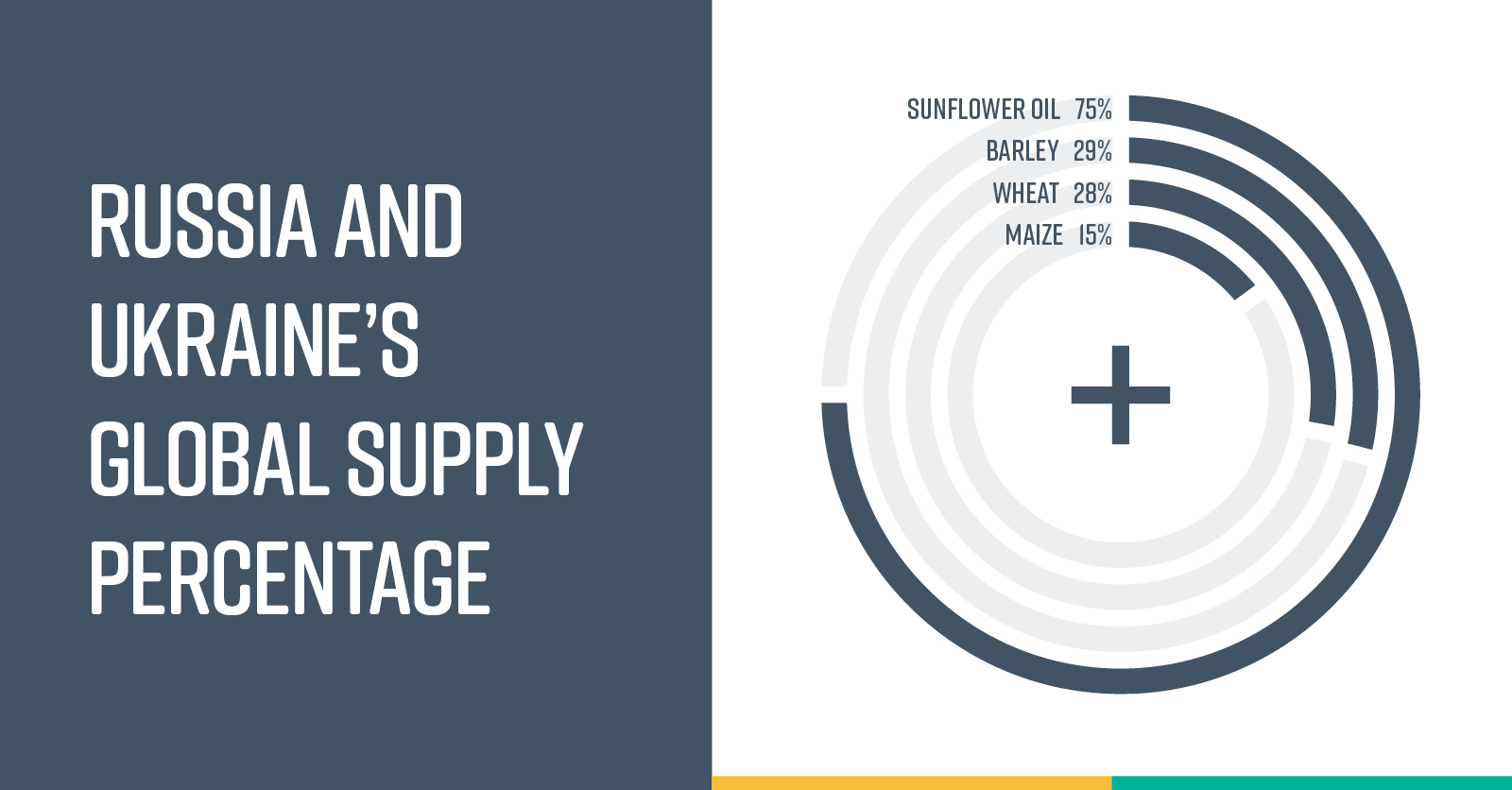

There will be incredible rises in the cost of staple commodities, such as wheat, barley, maize, and sunflower oil. In developing nations, these are essential staples and, for us, they are key ingredients that drive the cost of much of our food.

Back in May, UN Secretary General Antonio Gutierrez warned of ‘the spectre of a global food shortage that could last for years.’ He went on to say that the number of people who cannot be sure of getting enough to eat will rise by 440 million to 1.16 billion.

This is a new level of crisis that will affect everyone on the planet. It’s not really being talked about and the risk is not understood. Anybody in procurement that sources these commodities directly or depends on them should be looking at future planning scenarios right now.

A perfect storm

While the war in Ukraine is clearly a factor, a number of drivers have combined to create something of a perfect storm.

First, we – and many other countries around the world – depend on importing food and don’t produce enough to sustain ourselves. Russia and Ukraine supply about 28% of the world’s wheat, 29% of its barley, 15% of its maize and an incredible 75% of its sunflower oil. In fact, Ukrainian food exports provide the calories to feed around 400 million people on the planet. But exports have been disrupted by Russia blocking the port of Odesa.

Climate change is also part of the equation here. We are starting to see the effects and impacts of climate change. In China – the largest wheat producer on the planet – this year’s crops have been pretty much destroyed. Huge rains have delayed planting, leading to predictions of their worst crop in history.

In India – the world’s second largest producer – an extreme heatwave has killed crops. In the cereal growing areas of the US and France a lack of rain has threatened production.

We will need to grow more food in the UK, across Europe and in the US, rather than depend on certain supply chains around the world.

Should we have seen this coming?

It would’ve been hard to predict that Russia was going to invade Ukraine but perhaps we could have done more to understand risk. For too long we’ve accepted that globalization, global supply chains and trading around the world are sound and can be relied upon. Companies have accepted that there is a global marketplace open for business. In procurement, we’ve developed bilateral relationships with key trusted sources, securing supply through building relationships and working closely with producers. This is good practice, providing those markets work.

The problem is, we don’t have a plan B. Instead of establishing dual sources, we’ve built single relationships and channels of supply at a company and national level. Governments have established trade agreements with specific countries. What we are seeing now is that model needs to change. We can’t rely on one particular geography, country or producer. We need to think about all the different scenarios and how things could change.

The impacts of the pandemic and the invasion of Ukraine on global supply chains show they are quite fragile. It doesn’t take much to completely upset the way things flow and effectively eliminate large areas of the supply base. Moving forward, we can no longer assume that everything is going to carry on as it has done.

Cost increases

Inflation in the UK is close to 10% and around 1 to 1.3% of that is due to food price hikes. This will be worse for the poorest people.

The poor will get poorer. In developed nations, more people will rely on food banks. For developing nations, the threat is even more severe. Households in emerging economies typically spend about 25% of their income on food. In sub-Saharan Africa, that figure is 40%. If food prices rise, people can’t feed themselves.

As inflation bites, it costs more to get credit. Farmers can’t borrow money, so they’re not able to invest in crops. Currencies devalue and increase the cost of imports. Already poor countries are crippled with energy price hikes and can’t afford to subsidise the population. Poor nations will become drastically poorer. We’re set to witness spectacularly disproportionate social, political and environmental damage in the next two years.

What can we do?

Between February and August this year, around 23 million tonnes of corn and wheat was sitting in silos in Ukraine. That’s equivalent to the annual consumption of the world’s least developed countries. In August, following a huge effort by humanitarian bodies and various governments, cargo ships started departing Ukraine’s ports. To get this out, the approach to Odesa had to be de-mined, Russia had to allow Ukrainian shipping and Turkey needed to let goods pass through the Bosphorus Strait. Today, the situation regarding how much made it out is unclear and although a good proportion was shipped on the 108 or so cargo trips made, a significant amount still remains stuck.

Fortunately, there are other things we can do. For instance, we can make use of substitutes. About 10% of grains and 18% of oils go to make biofuel which, in normal times, is an environmentally sound thing to do. But right now, we need them to feed people. In fact, some Scandinavian countries have already changed their regulations around biofuel and opened the door to make that happen.

What we know for certain is that the future is uncertain. The supply base will be difficult and highly volatile. Perhaps the companies we work for are saying, ‘What are we doing about the food crisis?’ If they are not, we in procurement should be asking the same question. The answer will depend on the industry we are in. Clearly, in the food sector, this is critical. Elsewhere, we will be impacted but to a lesser degree.

Takeaways

Firstly, we need to accept that things will not return to where they were. Global trade will not go back to how it was. We’re likely to see a future of nations being protectionist, leading to increased volatility, more surprises and less security of supply. We have to start with the fact that the world’s gone crazy.

Secondly, we need to scenario plan and think of all the different things that could happen. What does it mean if we can’t get the supply we’re currently getting? What would different degrees of price hikes mean for us? And what would we do in response?

Next, we need to think about alternatives. How can we do things differently? How can we use substitutes? What other things can we do? This is about procurement getting close to what the organization does. So, if we process food, we should get involved in the design of that. We should be working with operations and R & D people to think about how we can do things differently. Perhaps we should consider what other relationships we could have and even change the entire model for sourcing? Can we think about acquiring suppliers? Can we vertically integrate? Can we start growing things ourselves?

It’s not such a crazy idea. Make versus buy is a fundamental part of procurement. Historically, we have assumed we can buy the crops that we need but perhaps we’re entering a time when, if you are a big food producer, you might want to own agriculture to deliver security of supply.

Finally, we must understand the global marketplace. What is happening around the world? What is driving cost fluctuations? We need to get to know the detail about supply chains and geographies so we can respond in an agile way that is faster than our competitors.

It’s time to get creative.