Jonathan O’Brien argues now is the time for procurement professionals to make sustainability a priority.

No doubt you will have heard the latest sustainability buzzwords. There are terms such as corporate social responsibility (CSR), environmental, social and governance (ESG) and even the circular economy. But what exactly is sustainable procurement?

Put simply, sustainability is the ability to exist constantly.

This means we need to stop thinking of an organization just making profit and start thinking more widely about its employees and how it impacts on people and the planet as a whole. Ultimately – and this may seem a bit apocalyptic – there is a real risk that the human race faces extinction if we do not address some urgent issues.

In truth, there is a lot of talk about sustainability but not enough action.

Globally, we need to be concerned with some huge issues, such as climate change, air pollution, biodiversity loss and over population.

Climate change

Very little is happening to address greenhouse gas emissions around the world. We are probably on target for around a three degree increase in the Earth’s temperature by 2050 (Gates, 2020).

The biggest cause is energy used in industry, particularly iron, steel and chemical production, and heating inefficient buildings, while burning fossil fuels in cars accounts for about 12% of total emissions (Ritchie & Rosser, 2020).

In 2020, during the pandemic, we actually saw a huge drop in global emissions. This shows it can be done.

In his book, ‘How to Avert a Climate Change Disaster’, Bill Gates says we have to get from 51 billion tons of greenhouse gases each year to zero, to be able to avert disaster (Gates, 2020).

In practice, this looks like more droughts, floods and wildfires, a billion more people in water scarce areas by 2050, and global food security under threat (World Meteorological Organization, 2020).

Air pollution

Emissions are also a major cause of air pollution which exceeds World Health Organization limits in places where 91 per cent of the world lives and accounts for 42 billion deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2016).

Biodiversity loss

Biodiversity loss is a big issue, too. About one million of the world’s eight million species of animals and plants are facing extinction, with much of this down to deforestation (IPBES, 2019).

According to current projections, if we continue on this path then, within a hundred years, we will lose everything as a result of displacing species, accelerating climate change and causing other issues.

You may regard the COVID pandemic as a once in a century event. But research suggests that, as we invade the forests, there is an increased likelihood of pandemics occurring more frequently. When species are removed, others become dominant, then animal viruses in remote parts of the world begin to come to the fore and connect more readily with man (Attenborough, 2020).

Over population

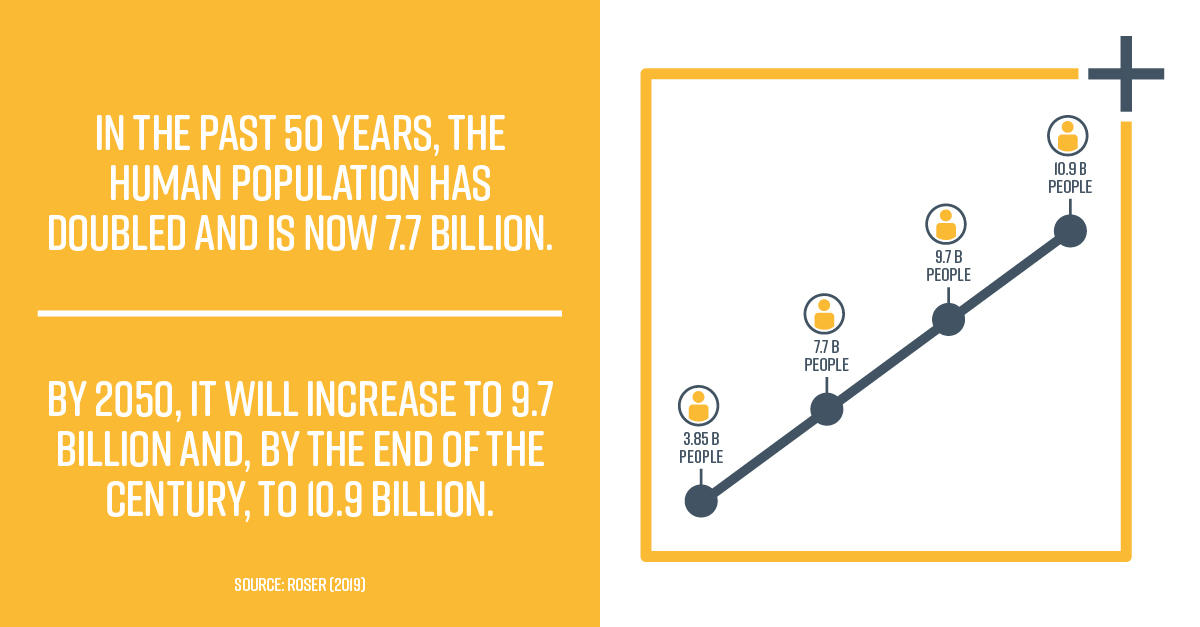

In the past 50 years, the human population has doubled and is now 7.7 billion. By 2050, it will increase to 9.7 billion and, by the end of the century, to 10.9 billion (Roser, 2019).

Another issue is over consumption. In the UK, we use about four times the resources of somebody in India. In the US, that figure is about nine times (Attenborough, 2020). As the population expands, there are simply not enough resources to sustain that level of demand around the world.

‘Situation Planet Earth’

When you bring all these things together, we are faced with an apocalyptic view of ‘Situation Planet Earth’ which threatens our food and water security. Developing countries will suffer most. There will be more pandemics, deaths from poor water quality, disasters and close to one billion climate migrants within the next 20 years, moving from areas that become uninhabitable. That will change our supply chains, increase volatility – especially with natural disasters – and change our attitude to responsibility for what is happening in this world.

Legislation

It may seem that nobody is doing anything about it.

Indeed, many countries of the world are not really on board. There are global efforts to try and change that. At Cop 26 in November, some of these issues will be discussed and we know this was a key discussion point in the south west of England recently during the G7 Summit where world leaders came together. There is a groundswell of understanding that it’s time to change. And opinion drives legislation that drives change. There are many new pieces of legislation around emissions that we will need to think about in the future.

Business responsibility

This is now on the agenda in the boardroom, whereas it wasn’t 20 years ago because it got in the way of business. As Milton Friedman, the economist and Nobel peace prize winner, once said, “The business of business is business”. He said, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business: to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits, so long as it stays within the rules of the game”.

That was the view in 1970 that drove many organizations. It was actually saying that shareholders need to decide what the organization does. More than just those who own the business, today we should consider everybody who has a stake in what a business does. That means all the people of the world who depend on the same resources. Our mindset here has changed. Organizations can choose to ignore this, but those that do probably don’t have a future.

Brand advantage

People are changing what, how and where they buy, in order to reflect their personal views. If organizations don’t listen, they’re going to sell less of whatever they’re producing, because it’s no longer in vogue. This is a fashion as well as an ethical consideration.

You could say, we need to do this because consumers won’t like us if we don’t. It will cause brand damage if we’re the company that’s exposed because of a problem in our supply chains. So, that’s a good reason to act, as is compliance with legislation. But also, sustainability at an organization and procurement level can bring value and create brand advantage.

We’re seeing the emergence of brands whose entire offering is based on sustainability, such as the clothing brand Patagonia, whose entire ethos is around adding value – not necessarily generating profit. The Body Shop was one of the first companies to set a brand based on considering what happens in its supply chains. More recent examples are Innocent Drinks and Bulb – a UK energy provider that guarantees all of the energy you buy is from renewable sources.

We are seeing a growth of brands where competitive advantage comes by being sustainable. We’re also seeing that environmental, social governance (ESG) type investments and sustainable companies are performing better than the rest of the stock market.

The role of procurement

If an organization is going to drive sustainability, 60% of what they need to do happens in the supply chain. The moment we start looking outside our organization, we have to be able to drive change in others. With our immediate suppliers we can begin to do that, because there is a contractual relationship, but when we look up the supply chain, to the original factory, plantation or raw material source, perhaps in another country where different laws apply, that becomes difficult. That is the part that companies are struggling with. So, the role of procurement is to respond to what the organization’s trying to do and figure out how we can make our supply chains, our suppliers, and what we buy more sustainable.

Making a difference

What do we buy? From whom do we buy it? What’s happening in our supply chain? Where are the risks? What are the things that we know could hurt us tomorrow? And what is the organization trying to achieve? What are its targets?

We can use hotspot analysis – looking on the supply side where we know there are problems and seeing if we are connected with any. We can think about geographies – areas of the world where there are known issues – and make sure that we’re not part of them. If we’re sourcing, say, cocoa beans from the Ivory Coast, we will know that this is a country where there have been forced labor issues. If we are sourcing gloves for hospitals, we will know that a Malaysian glove manufacturer was recently exposed by the Guardian for unacceptable conditions.

We must ask ourselves, are we buying things that contribute to deforestation, for example? Are we sourcing products that are known to generate problems, such as cocoa, fish, beef, soya, palm oil, chemicals and garments?

The key to this is to start to focus on it. We can’t change the world. We can’t do everything. It’s about picking – say – five things to work on. Five things to start to change. Five ways to make a difference.

Written by procurement expert, award-winning author of a series of acclaimed procurement and negotiation books, and CEO of Positive, Jonathan O’Brien.

Click here to discover our Sustainable Procurement program

References

Attenborough, D. (2020). Extinction: The Facts, BBC Studies – The Science Unit

IPBES, (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo (editors). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany.

Gates, B. (2020). How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, Allen Lane & Penguin Random House, UK.

Roser, M. (2019). Our World in Data, (2019). World Population Growth, 1700-2100, downloaded from https://ourworldindata.org/future-population-growth on 10/03/21.

Ritchie, H. and Rosser, M. (2020). CO2 and Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Our World in Data, downloaded from https://ourworldindata.org/co2-and-other-greenhouse-gas-emissions on 13/03/21.

World Health Organization, (2016). Ambient air pollution: a global assessment of exposure and burden of disease, WHO Press.

World Meteorological Organization, (2020). United in Science 2020 – A multi-organization high-level compilation of the latest climate science information, downloaded from https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/united_in_science on 17/03/21