Andy McMinn, Chief Procurement Officer for University Hospitals of Plymouth NHS Trust, Director of Procurement for the NHS Peninsula and Supply Chain Alliance, and NHS England and Improvement lead for spend analysis, talks about managing procurement through a pandemic in the National Health Service (NHS), the UK’s government-funded medical and health care service.

Imagine one minute you’re working flat out trying to manage procurement in the world’s number one healthcare system provider, and the next you’re fighting a pandemic.

A firm day in my memory is March 21, 2020. We’d just been told by our execs to get our back-office staff to move off-site. Fundamentally, we’re a caring organization and we had to think of our team’s safety and well-being. I was still in the office – an open plan space for about 120 people – and as I stood there on my own as everyone had gone home and thought, “What do I do now?”

That’s how it started. What followed was a whirlwind. It’s been a remarkable experience. Tough times, but really rewarding.

A question of scale

It’s worth understanding the scale of the hospital I work for. We have 2,800 product suppliers at the trust. We buy 80,000 products a year. We have 9,000 staff. On any day, pre COVID, we would have 30,000 staff, suppliers, patients and visitors on the hospital site. That’s like a small town! In the first month and a half, we worked in procurement and supply chain management without a single day off.

The eye of the storm

It’s fair to say we were in the eye of the storm and trying to get PPE was the immediate focus. Then, as the dust settled and national supply chains kicked in, we were still in containment mode but also looking at medium to long-term strategies around reshaping the hospital to deal with an expected increase in the numbers of COVID-19 patients we would need to treat and hopefully make better.

An agile response

When pressure hits, and this was pressure we had never seen before, you think you would have to compromise. I genuinely don’t think we did.

We’ve always been fast and responsive. Working off-site, we worked even faster because we were working longer. People went way beyond the call of duty. I wasn’t sure you got the best out of people with homeworking. I thought some would swing the lead. But that’s totally wrong. My team worked longer hours and, sometimes, seven days a week to get the job done.

PPE suppliers flooded the sector with quotes of 10 times what we would normally pay for a garment or gown. Prices were inflated and, for some suppliers, it was like the wild west, a race to secure inventory anywhere on the globe and to trade that inventory on for profit.

The importance of relationships

We didn’t buy from disreputable suppliers. We never ran out of a single PPE garment during the heaviest period with the highest volume of patients. We just reached out to our established network. It’s at times of stress and difficulty that you rely on the relationships you’ve strategically developed.

A few suppliers really helped us out – familiar ones that we knew we could trust and rely on, because we had a good trading history with them. There was risk for them sourcing unfamiliar products, but we worked with them to share that risk. For me, this was all about relationships.

Capital builds

PPE quickly settled down and our focus shifted to capital builds. We had to build a test and trace lab in Plymouth, normally a 12 month or even longer project. We had to do it in four. With only a couple of weeks’ lead time for mass vaccination centers to go live, I relied on our team’s competency and skill. Our approach to capital procurement was consistent but far faster and with more agility. Clearly, we threw more resource at it and stopped doing other work. But fundamentally we relied on the competencies and capabilities we’ve developed over the previous ten years.

The role of procurement

This didn’t change the role of procurement. The purpose was consistent. We’re here to help patients get better. That’s ultimately what my team enables. All that changed was the varying pressures on what we were buying and on the different, or changing, demands. But our purpose remained the same – time, cost, quality, value for money, managing risk, commercial risk, having good contracts and agreements in place. They were the same important set of outcomes and objectives that we try to achieve every day. Yes, we had to move really quickly. Yes, we were under pressure and sometimes that turned into stress. But I didn’t have to tell the team, “This is our differing purpose.” Our purpose remained the same.

There was an immense sense of satisfaction. I saw it in my team. I saw the feedback that we consistently received from the execs and the wider organization. One thing the pandemic has probably taught people outside of procurement, is the importance of procurement in the NHS.

On the first day the mass vaccination center opened I saw 700 people queuing, and thought, “700 people are going to be vaccinated and we’ve helped to make that happen.” There is no other emotion to feel than pride for that.

Centralization

There has been a shift to centralization. The Department of Health should be congratulated for the parallel ‘push’ supply chain it established for PPE supply. Every day a delivery would turn up with everything we needed. We’re under one NHS umbrella, but there are 235 different hospitals, ambulance trusts and health providers in the NHS in England. From a supply chain management perspective, the private sector has sales and production forecasting, inbound logistics and details of inventory coming in. In the NHS, we don’t see demand. No system captures it. The Department of Health set up the demand capture and we had to say each day how much PPE we’d used. That, I guess created the national demand profile, and national teams sourced against this demand profile. We could see the inbound inventory and the inventory on hand in the parallel supply chain at a national level. I think that approach to demand management will continue because it has been of real benefit.

When I came to the NHS in 2007 there was a body called The Procurement and Supplies Authority (PASA) that sourced all strategic procurement on behalf of the NHS, but it closed. Looking at what has been built this year around PPE sourcing, demand capture and medical device procurement, I think in hindsight and given what the DHSC has set up in the last year with central buying teams, that some may now believe closing PASA was a mistake. We’re now seeing more national procurement teams and strategies, and a move to centralization.

Portfolio Analysis

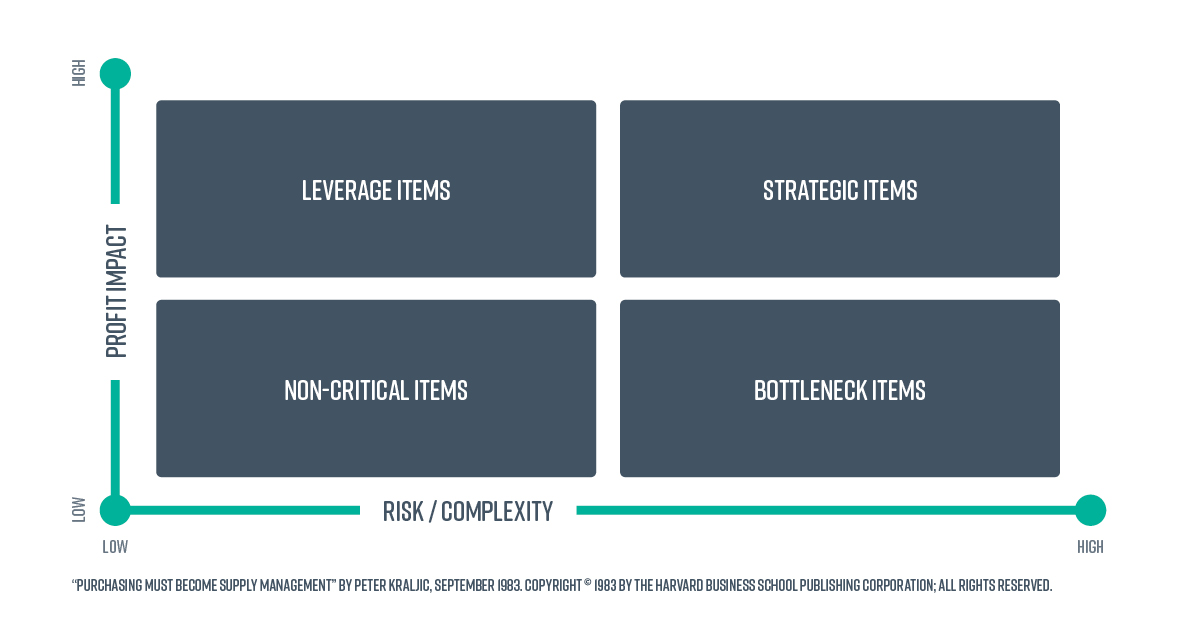

Using the Kraljic model (Kraljic, 1983), which segments a supplier base based on risk and probability, PPE would have always been categorized as Leverage, as an item in plentiful supply. Post Covid-19, if we were to run the analysis now, PPE would be seen as Strategic which would lead to a different procurement strategy. If you look at PPE as Strategic, the first thing you notice is that it is sourced from China with a three to four weeks’ ship time. You would therefore develop a UK landed manufacturer. I think you will see lots of onshoring happening and the manufacture of items we didn’t previously consider Strategic, leading to differing strategies.

If a pandemic happened again, I think we would have a national parallel supply chain, overnight, for products that are in demand. Consequently, scarcity of supply will be managed once for the nation.

Three things we can learn

- Plan for panic buying and manage communications, both upwards, through and across the organization and, crucially, with the public. We had panic consumption. People were hoarding and I was constantly saying to our execs, “Get the message out there. Don’t take more than you need – we have got plenty but be sensible with what you’re taking.”

- Identify the risks beyond PPE. What other things should I be worrying about? For example, products such as feeds for patients and renal supply fluids. Once PPE was settled, I should have stepped away and spent a day looking at spend analysis to see any shifting demands, allowing planning for containment strategies.

- Finally, presuppose that the team will do absolutely everything they can to make this happen, that they will pull out every stop, and work every hour to get it done, because they will, remembering other challenges about health and wellbeing in what can be a stressful situation.

When I reflect, I’m proud that we met some incredible demands and delivered value for money while, at the same time, treating every supplier fairly and equitably.

Of course, some stories in the press about how contracts were awarded reflected badly on our profession. I hope it doesn’t tarnish us because I think 95% of what we’ve done this year has been an incredible achievement. There has been a lot of success for the profession this year and much of which we can be proud.

References

Kraljic, P., (1983). Purchasing Must Become Supply Management. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/1983/09/purchasing-must-become-supply-management [Accessed 21 July 2021].